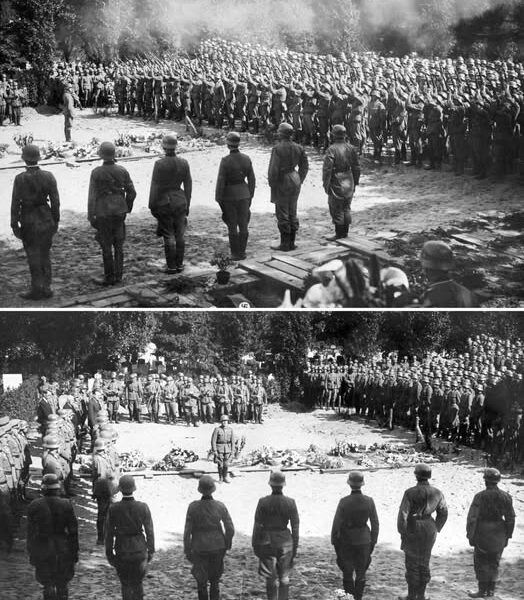

Memorial service for the 28 Germans who lost their lives in the Hindenburg disaster in 1937

About 10,000 members of German organizations lined the pier.

On May 11, 1937, memorial services for the 28 Germans who lost their lives in the Hindenburg disaster were held on the Hamburg-American Pier in New York City . Approximately 10,000 members of German organizations lined the pier. It appeared to be a mixture of Nazi Germany, American, and German-American Bund flags.

The Hindenburg, the massive German airship, caught fire while attempting to land near Lakehurst, New Jersey. Thirty-five people on board and one ground crew member were killed. Of the 97 passengers and crew on board, 62 survived.

The horrific incident was captured by reporters and photographers and replayed on the radio, in newspapers, and in newsreels. News of the disaster led to a loss of public confidence in airship travel and ended an era.

The 245 m (803 ft) tall Hindenburg used flammable hydrogen for lift, causing the airship to burn in a massive fireball. The actual cause of the fire, however, remains unknown.

German soldiers salute next to the coffin of Captain Ernest A. Lehmann, the former commander of the Zeppelin Hindenburg.

The fire

A few minutes after the landing lines had been dropped, RH Ward, the leader of the port landing party, noticed what he described as a wave-like fluttering of the outer cover on the port side between frames 62 and 77, which contained the gas cell number 5.

During questioning by the Department of Commerce, he testified that it appeared to him as if gas escaping from a gas cell was pressing against the cover. Ground crew member RW Antrim, who was on top of the mooring mast, also testified that he saw the cover flapping behind the rear port engine.

At 7:25 p.m., the first visible external flames appeared. Reports vary, but most witnesses saw the first flames either at the top of the hull directly in front of the vertical fin (near the ventilation shaft between cells 4 and 5) or between the aft port engine and the port fin (in the area of gas cells 4 and 5, where Ward and Antrim had seen the fluttering).

For example, Lakehurst Commander Rosendahl described a “mushroom-shaped flame flower” blooming in front of the upper fin. Navy Lieutenant Benjamin May, the assistant mooring officer atop the mooring mast, testified that an area directly aft of the aft port engine (where Ward and Antrim had reported the flutter) “seemed to collapse,” after which he saw streaks of flame followed by a muffled explosion, and then the entire stern engulfed in flames. William Bishop, a member of the Navy ground crew, described seeing flames “inside” the ship slightly above and aft of the aft port engine carriage.

On May 6, 1937, the German Zeppelin Hindenburg flew over Manhattan. A few hours later, the ship burst into flames.

Several witnesses inside the ship also saw the fire break out. Helmsman Helmut Lau, stationed at the auxiliary steering station in the lower fin, heard “a muffled detonation and looked up and saw, from the starboard side inside the gas cell, a bright reflection on the forward bulkhead of cell No. 4.”

Lau described the flames he saw during the investigation in Cell 4: “The bright reflection in the cell was from inside. I saw it through the cell. It was red and yellow at first, and there was smoke in it. The cell did not burst at the bottom. The cell suddenly disappeared due to the heat… The fire spread further downward and then entered the air.”

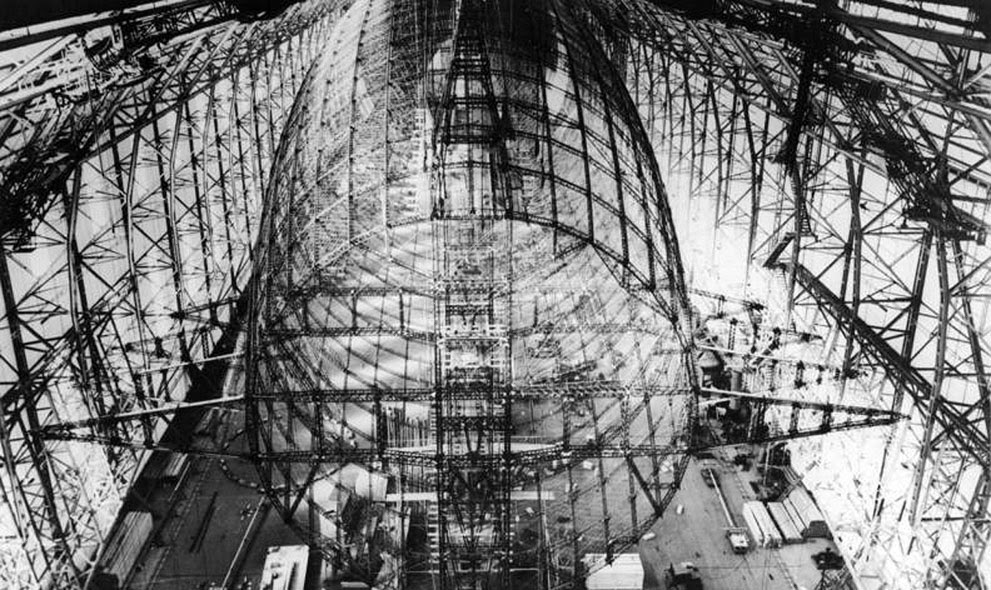

The steel skeleton of the new German airship “LZ 129” under construction in Friedrichshafen. The airship was later named after the late Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, the former German President.

The flame became very bright and the fire rose to the side, more to the starboard side, as I recall, and I saw that pieces of aluminum and fabric were thrown up with the flame.

At the same moment, the front and rear cells of Cell 4 [Cell 3 and Cell 5] also caught fire. Pieces of girders, molten aluminum, and pieces of fabric began to fall from above. The whole thing lasted only a fraction of a second.”

The fire spread rapidly and soon engulfed the ship’s stern, but the ship remained horizontal for a few seconds before the stern began to sink, pointing its nose upward toward the sky. A welding torch filled with flames shot out from the bow, where twelve crew members were stationed, including the six who had been sent forward to keep the ship in shape.

On the port and starboard promenades of the passenger decks, where many passengers and crew members had gathered to watch the landing, the rapidly increasing roll of the ship caused passengers and crew members to crash into the walls, furniture, and each other. Passenger Margaret Mather recalled being thrown five to six meters against the rear wall of the dining room and being pushed against a bench by several other people.

The Olympic rings on the side advertised the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.

The Aftermath

Before the Hindenburg disaster, the public seemed remarkably lenient toward the accident-prone Zeppelin, and the glamorous and fast Hindenburg still aroused great enthusiasm despite a long list of previous airship disasters.

But while airships like the British R-101, on which 48 people died, or the USS Akron, on which 73 people died, crashed at sea or under cover of night, far from witnesses or cameras, the Hindenburg crash was captured on film, and millions around the world saw the dramatic explosion that destroyed the ship and its passengers.

And despite its romance and grandeur, the Hindenburg was already technically outdated before it even flew. On November 22, 1935—three months before the Hindenburg first took flight—Pan American Airways’ M-130 China Clipper made the first scheduled flight across the Pacific.

The longest route, the 2,400 miles from San Francisco to Honolulu, was longer than the distance required to cross the North Atlantic. In fact, Pan Am’s M-130 was designed for the Atlantic, not the Pacific; only political (not technological) considerations prevented Pan Am from launching a transatlantic service in 1935. The British denied Pan Am landing rights until Great Britain had an aircraft capable of performing the same flight, but Great Britain was far behind America in developing a long-range airliner.

On May 6, 1937, at approximately 7:25 p.m. local time, the German Zeppelin Hindenburg caught fire while en route to the anchorage of the U.S. Navy airfield in Lakehurst, New Jersey. The airship was still about 60 meters above the ground.

As the rising hydrogen gas escaped from the Hindenburg’s tail and burned, the tail sank to the ground, sending a burst of flames through the nose. The ground crew below fled the inferno.