By G. Paul Garson

It was Napoleon Bonaparte who supposedly said, “An army travels on its stomach.” Eager to feed his army’s stomachs more efficiently, the French general devised an interesting solution to the problem in 1795. He sponsored a competition and offered a cash prize to the first successful demonstrator of a method of safely storing food and thus making it portable. It took 14 years for the prize to be awarded. In 1809, French chef Nicolas Appert invented a method of preserving food in glass containers. In the usual European competition, the British raised the bar just a year later by developing the metal can. However, it took another 76 years before someone invented a dedicated can opener. In World War I, German soldiers used hammers and chisels, along with various sharp and blunt instruments, to open their steel cans, but in 1925, the modern serrated-wheel can opener came into use—just in time for World War II, when the Germans and French were fighting each other again. In World War II, however, German rations had to ensure an efficient and nutritious supply of food for troops and the civilian workforce at home. They could mean the difference between victory and defeat in a battle or a war. (With Military Heritage magazine , you’ll receive a personalized guide through all the key moments in history, from Napoleon to D-Day.)

To this end, German scientists, including agricultural scientists and nutritionists, were tasked with developing a food production plan that was consistent with the Third Reich’s ambitions to conquer Europe and ultimately transform the East into a single large farmland for Greater Germany.

Minister of Food of the Reich

Richard-Walther Darre was initially entrusted with the management of these far-reaching programs. Born in Argentina in 1895, the German had studied both in Germany and at King’s College in England and served as an artillery officer in World War I. As a qualified agronomist, a fervent proponent of the National Socialist “Blood and Soil” ideology, and an early friend of SS chief Heinrich Himmler, Darre had good prospects for advancement.

He owed his popularity primarily to his books, in which he championed the Nordic (i.e., German) peoples, especially the German peasants, as the founding fathers of European culture. Darre, himself a pig farmer, shared a similar mindset to Himmler, a former chicken farmer. In 1933, the year the Third Reich was founded, he was appointed both Reich Farmers’ Leader and Minister of Food and Agriculture. He also wrote a book on pigs in ancient folklore and other works in which he expounded his racist views and the means of ensuring racial health.

However, Darre’s inability to organize Germany’s food supply led to his fall from favor with Hitler. In 1942, he was replaced by the more pragmatic Herbert Backe, who remained Reich Minister of Food until the end of the war. His main focus was organizing food supplies for the war against the Soviet Union, which included supplying the German military.

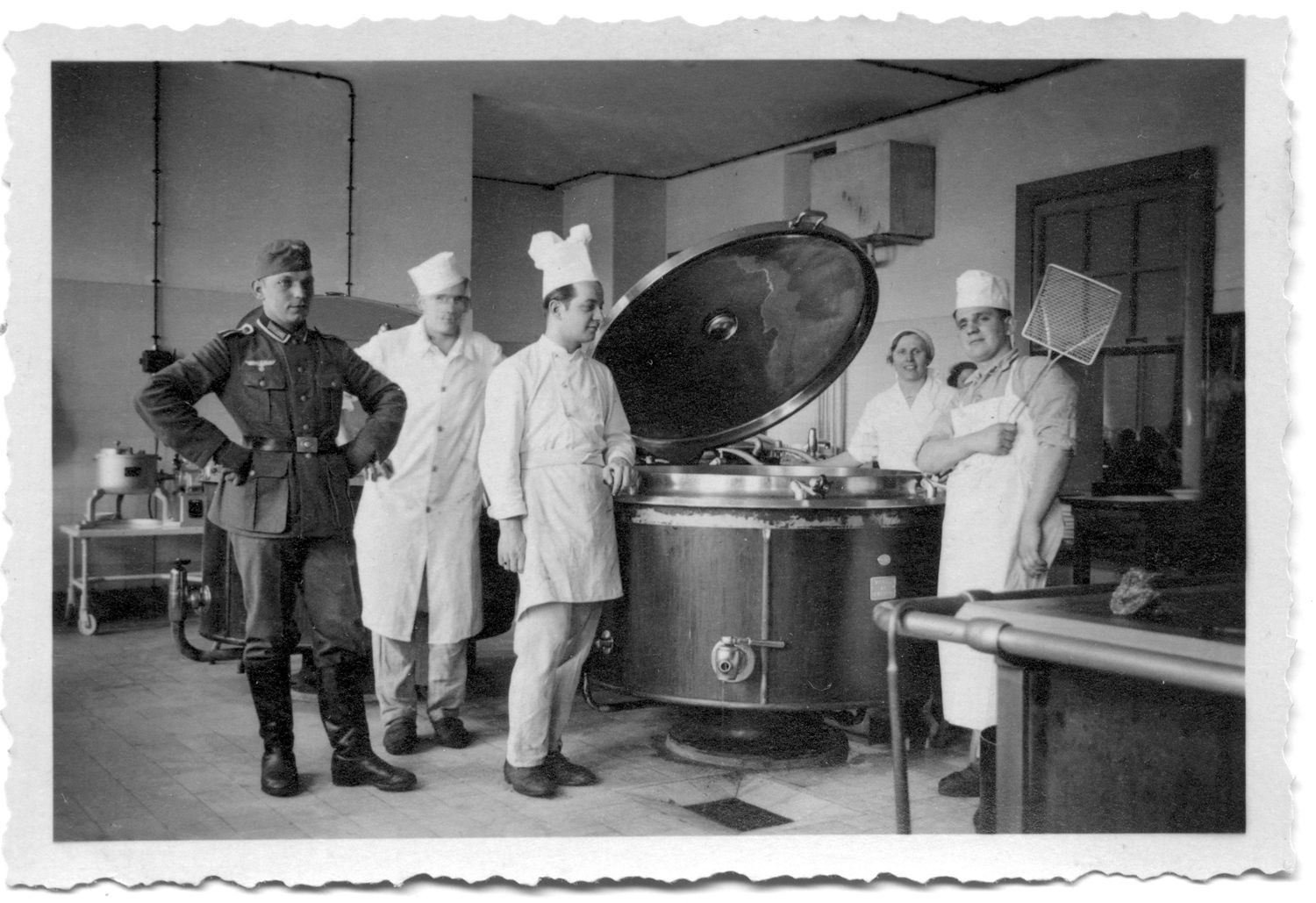

Combat rations of the German Wehrmacht

In general, regular German soldiers received a scientifically formulated, high-calorie, high-protein diet. Typically, each soldier carried a day’s supply of the so-called ” Halbierserne ” or “Iron Ration,” which contained a 300-gram can of meat and a 125- or 150-gram unit of hard bread. The canned meat could be Schmalzfleisch (pork), Rinderbraten (roast beef), Turkeybraten (turkey), or Chicken . In addition, there were canned meats, the contents of which were generally and therefore ambiguously referred to as “canned meat,” which allowed for a variety of interpretations.

Another staple of the German army was pea sausage, a nutritious soup pressed into pellets and packaged in six-packs. One pellet was crushed and added to half a liter of boiling water. A minute later, the instant soup was ready. Alternatively, condensed tomato soup was available from a can if a field kitchen was unavailable. Soldiers often added half a can of water and half a can of milk to enhance the flavor. Milk was also available in cans.

Elite troops received ration supplements such as the combat pack for paratroopers . This consisted of real canned cheese, but was only issued before a combat mission. The special pack also contained two cans of ham pieces, a bar of substitute energy food, milk coffee (milk powder and instant coffee), crispbread , and candy.

The SS had its exclusive version of German rations, whose cans were treated with a special coating for extreme climatic conditions and coated with a rust-inhibiting yellow-brown lacquer. The standard German ration for SS units in the field consisted of a four-day supply: about 750 grams of gray bread , 170–280 grams of meat or sausage , about 140 grams of vegetables, 140 grams of butter, margarine, jam, or hazelnut paste, either real coffee or coffee substitute, five grams of sugar, and, oddly enough, six cigarettes, despite the anti-smoking stance of the SS leadership on the grounds that cigarettes served as a “nerve tonic” for troops under combat stress. There were also other special SS supplements, such as canned liverwurst, a high-quality liver spread.

The Third Reich’s anti-smoking initiatives, part of a general health campaign that also included measures against alcohol and workplace pollution, originated from the research of German scientist Franz H. Müller in 1939. Müller published the world’s first epidemiological case-control study demonstrating a link between tobacco smoking and lung cancer. The various health programs aimed to reduce sickness absence and costs, produce fit and healthy workers and soldiers, and “preserve the racial health of the people.”

The peak of German agriculture

The Reich Labor Service (RAD) was a compulsory paramilitary organization established by law in June 1934. Men and women aged 19 to 25 were required to work with farmers in the fields or perform other labor for six months as part of a strictly disciplined program. They were drilled as soldiers but carried spades. With the RAD, Hitler solved Germany’s massive unemployment problems, provided cheap labor, and indoctrinated youth. Through the RAD, he was able to circumvent the restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles after the First World War, which was intended to limit German military expansion. It also offered the opportunity to introduce the youth of the Third Reich to a military model for later integration into the Wehrmacht, Kriegsmarine, Luftwaffe, and SS.

In the early years of Hitler’s regime, beer consumption rose by 25 percent in a country with high beer consumption, suggesting an improved economy. Wine consumption doubled, especially after the conquest of France, and champagne sales quadrupled.

Soldiers were allowed to send packages home from their posts in occupied territories, triggering a flood of shipments from France, Holland, Belgium, Greece, the Balkans, and Norway. By early 1942, German families were receiving an abundance of food, including fresh fruit, whole hams, and even lard, butter, and chickens—not to mention non-food items such as silk stockings, perfumes, shoes, and high-quality soaps. All of this helped fuel a thriving black market in Germany.

Soldiers serving alongside their Italian allies occasionally sampled their food, including what they called Mussolini potatoes or “Mussolini potatoes,” the German term for macaroni and spaghetti.

Sweet treats of all kinds were highly sought after, and some even served medicinal purposes. Soldiers returning from a particularly strenuous mission or deployment, for example, were entitled to the supplementary rations for front-line soldiers. Packaged in a pink bag, they contained individually wrapped fruit candies. A soldier’s ration also included Kandiezucter, a sugar candy issued as a sugar ration.

Another candy, the lemon-flavored Lemon Drops, helped front-line troops during adverse weather conditions and was also distributed to wounded soldiers at medical stations. Another popular treat was the Vivil peppermint candy, which was included in Army ration packs and Luftwaffe flight and survival packs. Vivil, due to its relative mildness, was preferred to other, stronger peppermints when the smell of alcohol needed to be masked. Luftwaffe personnel also received Waffelgebäck, a 100-gram chocolate wafer, which was often used as a barter item with other branches of the Wehrmacht.

German rations supply the home front

Fearing that poor morale at home would undermine the war effort (as it had in World War I), the Nazi regime went to special lengths to ensure that war rations were the highest in all of Europe. Countries conquered by the German military machine were deprived of their food not just to feed German citizens, but as part of an overall plan to cause widespread starvation among the subjugated peoples in order to “depopulate” the Slavic lands and make room for German Lebensraum and new Aryan landowners. The German Ministry of Agriculture’s 1940 plan called for the deaths of approximately 30,000,000 Russian civilians. On the way to this goal, approximately 3,000,000 Soviet prisoners of war died by early 1942, mostly from starvation. Hundreds of thousands more of all nationalities slowly starved to death in concentration and forced labor camps throughout Europe.

In the final stages of the war, as food supplies on the German home front were rationed and becoming increasingly scarce, various “fillers” were added to loaves of bread to give them more substance (if not nutrients). Substitute coffee was also made from chicory, as well as roasted and ground acorns, beechnuts, barley, and even chickpeas and oats.

Most lacked caffeine, which offered no real benefit to the soldiers, who had to survive on few calories and sleep. Civilians received their sugar and meat rations measured to the centimeter. Therefore, many kept dachshunds —the name given to cats bred for food—often in cages on roofs.

Incidentally, in September 2009, the German government overturned Nazi-era treason convictions and dropped charges against German citizens and soldiers convicted of “harming the state,” including black market traders.