How Charles Coward saved Jewish prisoners from the Nazis and became known as the “Count of Auschwitz”

After being captured by the Germans in 1940, Charles Coward spent the rest of World War II as a prisoner of war, but still rescued hundreds of Jewish prisoners from Auschwitz.

LSU Law Digital Commons Charles Joseph Coward testified as an eyewitness.

Charles Coward was a British soldier during World War II who rescued hundreds of Jewish prisoners from Auschwitz. He was captured by the Germans in 1940 and spent most of the war either escaping his German captors or helping to rescue other prisoners until his liberation in 1945.

Until 1943, Coward made several escape attempts but was repeatedly captured. That same year, the Germans sent him to Auschwitz, where, due to his fluent German, he was appointed Red Cross liaison for all British prisoners of war. He soon became known as the “Count of Auschwitz.”

The position offered him relative freedom of movement and correspondence. He wrote coded messages to the British War Office, reporting his observations. He also organized several daring escape attempts by Jewish prisoners from the labor camp and even claimed to have once penetrated the Jewish zone.

On this mission, he witnessed some of the worst Nazi atrocities. His observations formed the basis of his testimony at the Nuremberg Trials, where several executives of the chemical company that operated its part of the Auschwitz concentration camp were convicted.

How Charles Coward was captured

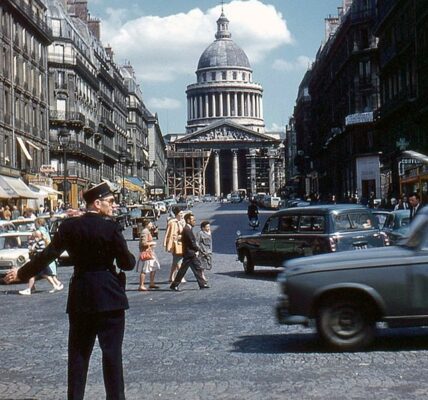

Wikimedia Commons The Battle of Dunkirk led to the British retreat and evacuation from France in 1940.

Charles Joseph Coward was born in England in 1905. He joined the British Army in 1937, two years before the outbreak of war. Coward served in the 8th Reserve Regiment of the Royal Artillery. At the beginning of the Second World War, he was a Quartermaster Battery Sergeant Major.

Coward was part of the British Expeditionary Force sent to reinforce France in 1939. In May 1940, they intervened when German troops invaded. After only a few days of fighting, the British and French were forced to retreat to the French coast.

On May 21, the Germans attacked the French port of Calais. The Allies were forced back to Dunkirk, where most managed to escape to Great Britain. Coward, however, surrendered and was captured in Calais.

He had to serve the rest of the war as a prisoner of war. Coward’s only advantage was his command of the German language, which likely kept him alive during the war.

Cowardly daring escape attempts

Federal Archives British prisoners of war captured in Calais in 1940.

Even before being sent to his first POW camp, Charles Coward managed to escape. After his imprisonment, he made seven more successful escape attempts . However, each time he was recaptured before he could leave German-occupied territory.

But an escape almost worked when Coward left his POW camp disguised as a German soldier. Injured from his escape, he was taken to a hospital for treatment. Because Coward spoke fluent German, the hospital staff treated him like any other German soldier wounded in battle.

In fact, the operation was so successful that Coward was awarded the prestigious Iron Cross, the highest German military award for courage and bravery, in the field hospital.

Despite his excellent language skills, Coward was soon exposed as a fraud and sent back to prison. But the Germans had had enough of Coward’s escapades. This time they transferred him to a more secure concentration camp.

Transfer to Auschwitz

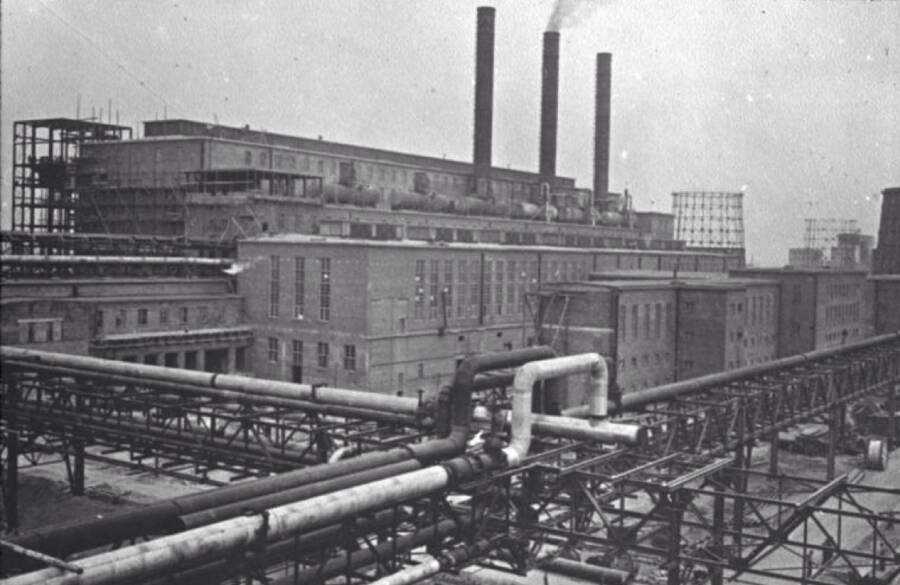

Bundesarchiv/Wikimedia Commons The IG Farben chemical factory in Auschwitz-Monowitz, where Charles Coward was deported in 1943.

The Nazis sent Coward to the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland. Auschwitz consisted of two sections : the Birkenau extermination camp, where prisoners were sent to be killed. The other was the Monowitz labor camp, which was divided into two sections, one for Jews and one for non-Jews.

The prisoners at Monowitz were forced laborers who slowly toiled to death to produce goods for the German war effort. The camp was run by the German chemical company IG Farben, which produced the deadly Zyklon B gas used to kill Jewish prisoners in gas chambers.

Thanks to his fluent German, Charles Coward continued to be of use to his captors. He was appointed Red Cross liaison officer and was responsible for British prisoners of war.

Coward was responsible for distributing Red Cross relief supplies such as food and medicine to prisoners of war. An estimated 1,200 to 1,400 British prisoners were held at Auschwitz, and his new role gave Coward more access to the camp than most other prisoners.

The camp administration even allowed Coward to write letters to his “friend” William Orange in his native Great Britain. What his German guards didn’t know was that William Orange was a code name for the British War Office. In his letters, Coward used coded messages to tell “William Orange” everything he saw at Auschwitz.

How Charles Coward smuggled Jewish prisoners out of Auschwitz

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum/Flickr Nazi guards process Jewish prisoners at Auschwitz, 1944.

It wasn’t long before Coward began helping others. First, he began smuggling extra food to the hungry prisoners whenever possible.

One day, Coward received a smuggled letter from a British-Jewish doctor pleading for help. The doctor, Karel Sperber, was born in Germany but had fled to England after the German invasion of Czechoslovakia. He later joined the crew of a British merchant ship as a doctor, but was captured after the Nazi attack on the ship.

As a British civilian, Sperber should have been housed in the camp’s POW wing. Instead, the Nazis took him to the Jewish camp, which housed approximately 10,000 people. Coward answered the call and managed to sneak into the Jewish section to find the doctor.

And although Coward could not find the doctor in the large crowd, he witnessed the horrific conditions of the Jewish slave laborers in the camp and vowed to help them.

Coward had a plan. The Red Cross had given chocolate to the prisoners of war. Chocolate was a rare treat in the POW aid packages. But instead of distributing all of it to British POWs, Coward bribed the camp guards with a portion. In exchange for the chocolate, the guards granted him access to the bodies of non-Jewish prisoners.

There were nightly marches of weak Jewish workers from the labor camp to the gas chambers at Birkenau, about eight kilometers away. Some healthy workers sometimes sneaked into the nightly processions in a daring but dangerous maneuver. The healthy men abandoned the march and hid in ditches.

Coward gave the men the corpses’ clothing and papers. The bodies were then placed in the ditch, dressed in Jewish workers’ uniforms. When the Nazis counted the bodies along the route, it appeared as if all participants in the march had been accounted for.

According to Charles Coward’s own estimates, he saved over 400 lives in this way.

Witness statements at the Nuremberg trials

Yad Vashem Charles Coward in Israel receiving the Righteous Among the Nations award, 1962.

When the Soviets invaded Poland in January 1945, Charles Coward and the other prisoners of war were forcibly driven westward toward Germany in bitter cold. He and his fellow British prisoners were eventually liberated in Bavaria.

After the war, Coward was called to testify as an eyewitness to Nazi atrocities at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials. Coward described in detail the conditions at Auschwitz, the treatment of Allied prisoners of war and Jewish prisoners, and the locations of the gas chambers.

A book about Coward’s wartime exploits, “The Password Is Courage,” was published in 1954 and made into a film in 1962, starring Dirk Bogarde as Charles Coward.

Coward died in 1976, but before that, he became the first British citizen to be named “Righteous Among the Nations” in Israel. A tree was planted in his honor at the Holocaust Museum for his efforts to save Jewish lives. Hence, he was nicknamed the “Count of Auschwitz.”

In a 2008 speech to the House of Commons, Israeli President Shimon Peres praised Coward for saving his father’s life. Coward, Peres said, “was not only the savior of many Jews, but also our father’s comrade in arms.”