Adolf Eichmann awaited his trial in Israel in 1961.

Adolf Eichmann inspired Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase “The Banality of Evil .” As an official in Nazi Germany, he was tasked with carrying out the “Final Solution” and organized the arrest of Jews from across Europe and their transport to concentration camps for murder.

Other observers also felt that he approached his task with the same bureaucratic, emotionless, and formal attention to detail that he would have shown in, say, road maintenance or food rationing.

Eichmann joined the Nazi Party in Linz, Austria, in April 1932 and rose through the party hierarchy. In November 1932, he became a member of Heinrich Himmler’s SS, the Nazi paramilitary corps. After leaving Linz in 1933, he attended the Austrian Legion School in Lechfeld, Germany.

From January to October 1934, he was assigned to an SS unit in Dachau and was subsequently appointed to the SS Security Service in Berlin, where he worked in the Jewish Affairs Department. He rose steadily in the SS and, after the Anschluss of Austria (March 1938), was sent to Vienna to liberate the city of Jews.

A year later, he was sent to Prague on a similar assignment. When Himmler established the Reich Security Central Office in 1939, Eichmann was transferred to his Department for Jewish Affairs in Berlin.

In January 1942, a conference of high-ranking Nazi officials was convened in a lakeside villa in the Berlin district of Wannsee to organize the logistics of what the Nazis called the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.”

Eichmann was to coordinate the details. Although it was not yet widely known that the “Final Solution” consisted of mass executions, Eichmann had been appointed de facto chief executioner.

He then organized the identification, gathering, and transport of Jews from throughout occupied Europe to their final destinations in Auschwitz and other extermination camps in German-occupied Poland.

Eichmann’s paths, as his victims once knew, were restricted by barbed wire.

After the end of World War II, Eichmann was captured by US troops. However, he managed to escape from a prison camp in 1946. After living in Germany under a false identity for several years, Eichmann traveled via Austria and Italy to Argentina, where he settled in 1958.

He was arrested by Israeli intelligence agents near Buenos Aires, Argentina, on May 11, 1960; nine days later, they smuggled him out of the country and brought him to Israel.

After the controversy over this Israeli violation of Argentine law was settled, the Israeli government arranged for his trial before a three-judge special court in Jerusalem. Eichmann’s trial was controversial from the start.

The trial—before Jewish judges and by a Jewish state that only came into existence three years after the Holocaust—gave rise to accusations of retroactive justice . Some called for an international tribunal to try Eichmann, others wanted him tried in Germany. But Israel persisted.

During interrogation, Eichmann claimed not to be an anti-Semite. He declared that he disagreed with the vulgar anti-Semitism of Julius Streicher and other contributors to the magazine Der Stürmer . He portrayed himself as an obedient bureaucrat who was simply fulfilling his assigned duties.

Eichmann determined who would board the trains to Auschwitz and Treblinka immediately and who would be deported later. He ensured that his men coordinated the transports. In the offices of his department on Kurfürstenstrasse in Berlin, figures depicting the current status of the genocide hung.

Regarding the charges against him, Eichmann insisted that he had not broken any law and that he was “the kind of man who could not lie.”

He denied responsibility for the mass killings, saying, “I couldn’t do otherwise; I had orders, but I had nothing to do with this matter.” He described his role in the extermination unit only evasively, claiming he was only responsible for transport. “I never claimed to have been ignorant of the liquidation,” he testified. “I merely said that Office IV B4 [Eichmann’s office] had nothing to do with it.”

While Eichmann denied actual responsibility, he seemed proud of his ability to establish efficient procedures for the deportation of millions of victims. But Eichmann’s job was not to follow orders to coordinate an operation of this magnitude.

He was a resourceful and proactive manager who relied on various strategies and tactics to secure scarce cattle cars and other equipment for the deportation of Jews when equipment shortages threatened the German war effort. Time and again, he developed innovative solutions to overcome obstacles.

His trial lasted from April 11 to December 15, 1961. Eichmann was sentenced to death—the only death sentence ever imposed by an Israeli court. Eichmann was hanged on May 31, 1962, and his ashes were scattered at sea.

While the Eichmann trial itself was controversial, it was followed by an even greater controversy. In 1963, political scientist Hannah Arendt added a frightening (and ultimately controversial, because often misunderstood) term to the international vocabulary: “The Banality of Evil.”

Arendt coined this provocative phrase in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem , which in turn grew out of her reporting for The New Yorker on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the most important Nazi officials behind the Holocaust.

An image of a Red Cross travel document issued to a certain Ricardo Klement, a cover name for Adolf Eichmann. This document allowed Eichmann to leave Europe via Italy and travel to Argentina.

From Arendt’s perspective, Eichmann was both a monstrous and pathetic creature, the embodiment of the Third Reich’s singular obsession with mass murder on the one hand and routine, businesslike documentation and organization on the other.

After all, this was a man who, during the trial, relied entirely on the now infamous defense that he was merely “following orders” when he organized the transport of Jews and other “undesirables” to the Nazi death camps.

For Arendt, such reasoning was not proof of pure, unmitigated evil. Rather, it demonstrated that subordinating one’s humanity and decency to a system as murderous as that of the Third Reich was nothing more (or less) than a renunciation of morality in the face of something greater.

(Not, Arendt emphasized, in the face of something better or more admirable, but in the face of something greater. After all, Eichmann admitted that his ruthless efficiency in implementing the “Final Solution” stemmed as much from a desire to advance his career as from a deep ideological sympathy with the Reich’s stated aims, a system based on genocide.)

Critics of Arendt’s “banality of evil” formulation, meanwhile, argue that her theory, if extended to its extreme, could actually absolve war criminals of any guilt. “If someone like Eichmann is ultimately just like everyone else,” they reason, “and we are all potential Nazis, how can we judge his innocence or guilt?”

The only problem with this thesis is that Arendt, in Eichmann in Jerusalem , undermines it in advance by pointing out that while we may all be capable of Nazi-like cruelty, the whole point of free will and a moral life is that we choose whether or not to act cruelly.

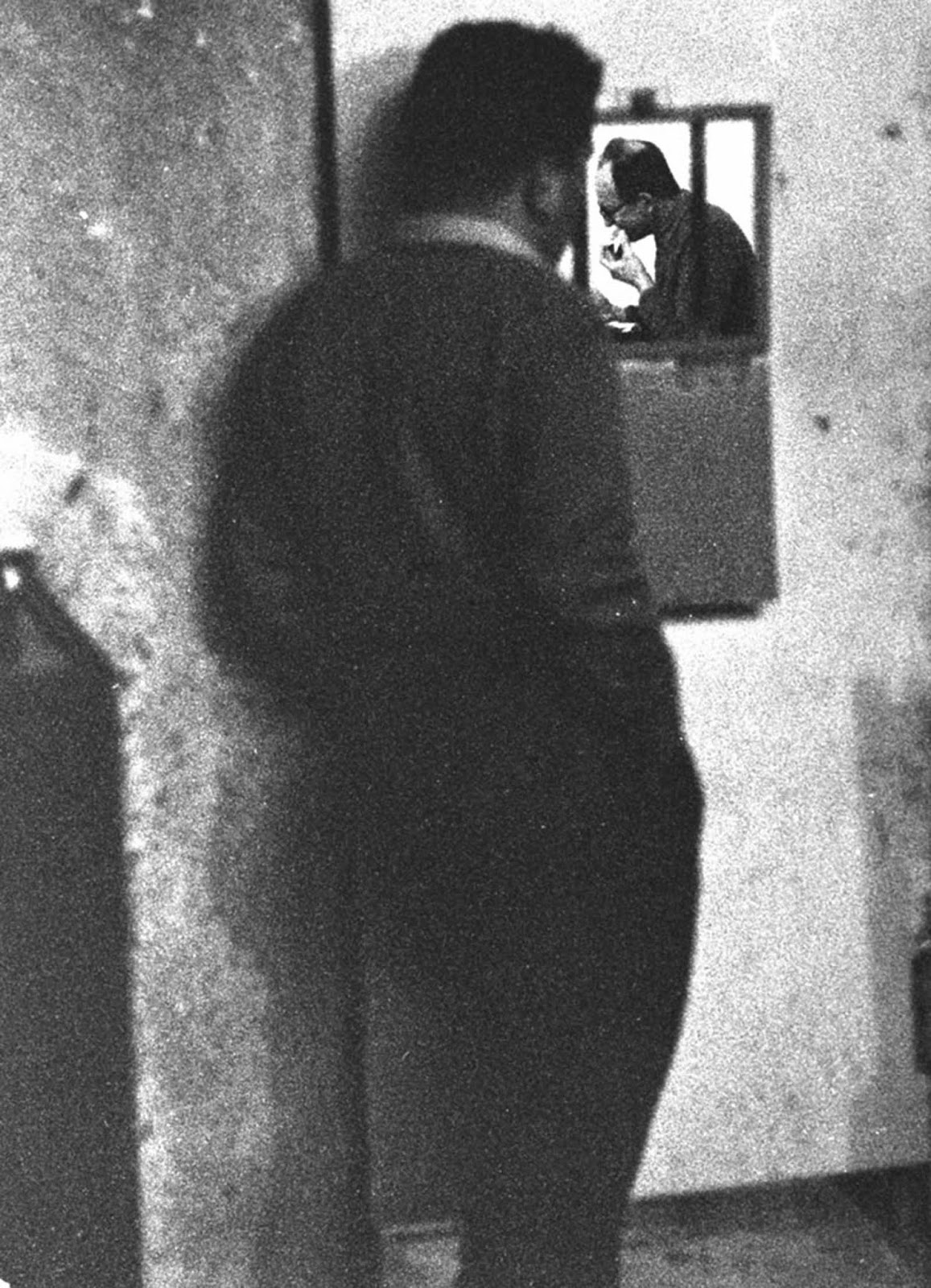

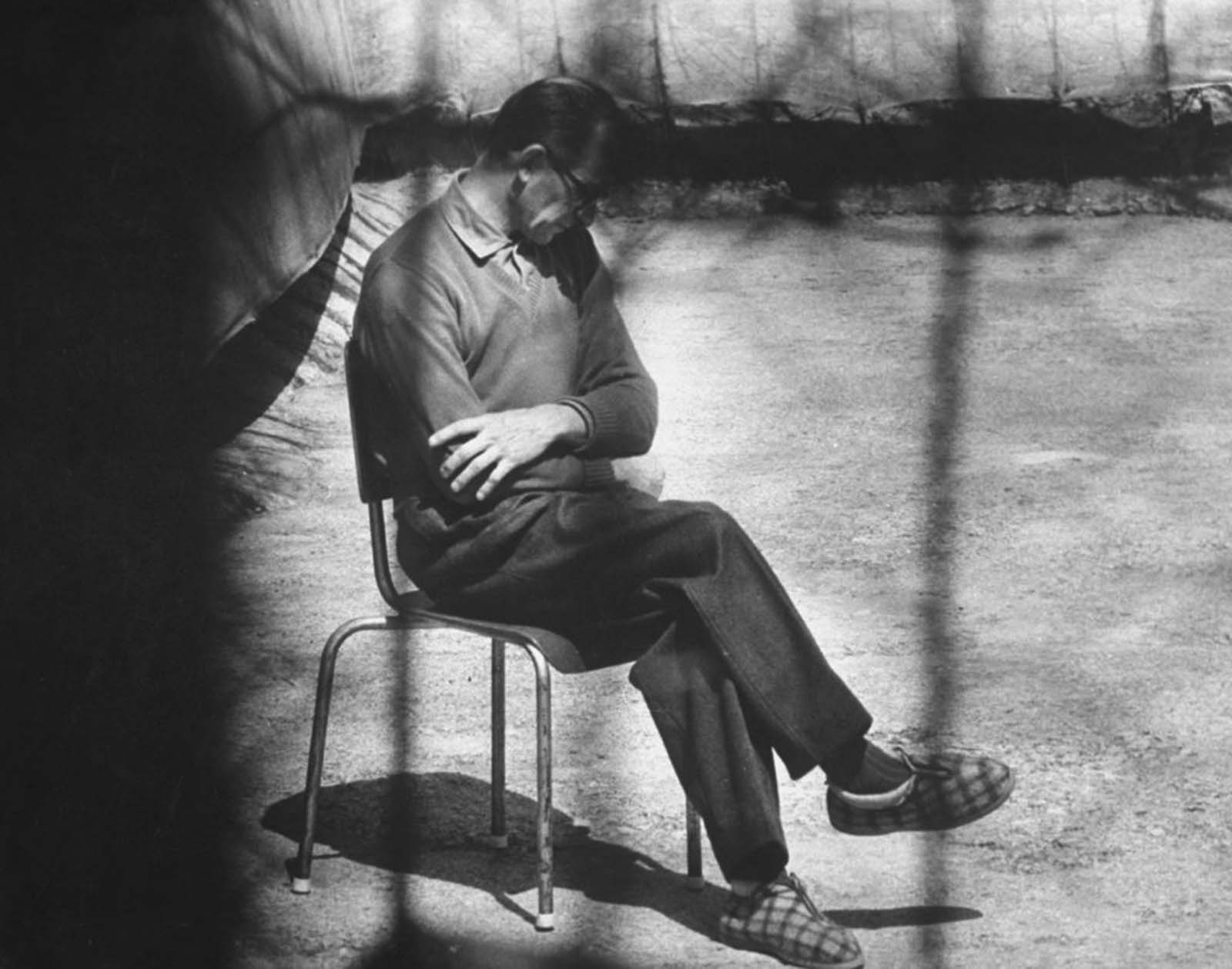

In this article, we present images of Eichmann in prison: raw, strangely intimate photographs by Albanian photographer Gjon Mili, which document the “arch-war criminal” (as LIFE magazine described him) going about his everyday business: reading, writing, washing, eating, all the while fully aware—like much of the world—that the gallows awaited him at the end of his trial.

Eichmann ate alone but watched from outside. Most of the guards didn’t speak German and were forbidden to speak to him.

His daily bath was a makeshift affair, but part of the prison’s strict routine.

Eichmann’s daily routine included a medical examination after breakfast under the supervision of a guard.

As part of his housework, Eichmann mopped the bathroom floor in his prison near Haifa.

Eichmann hung self-washed shirts and underwear over the bars of a window.

Reading and writing were both permitted and Eichmann concentrated on books about the Nazi regime.

During Passover week, shortly before his trial, Eichmann cut breakfast margarine into pieces while a guard placed it on his tray.

When prisoner Eichmann attempted to speak during his daily walk outside, he was met with stony silence from the prison guards. In good weather, he was allowed to take a half-hour walk outside every day.

Adolf Eichmann awaited his trial in Israel in 1961.

Sitting around outside gave Eichmann plenty of time to think and reflect.

Adolf Eichmann in prison, 1961.

While he waited for his trial for almost a year, he spoke to no one except Israeli police interrogators and his lawyers.

While Eichmann slept, he was watched by an observer and the only light bulb on the ceiling burned all night.

Adolf Eichmann awaited his trial in Israel in 1961.

Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann stands in a protective glass booth during his trial in Israel in 1961. Eichmann was convicted and ultimately executed for his role in organizing and perpetrating the Holocaust.

Adolf Eichmann listens to the verdict in his trial in December 1961.

In the last days of the war and immediately afterwards, Eichmann and other SS members found refuge on the shores of Lake Altaussee in Austria.

Eichmann was found guilty on all counts and executed by hanging on June 1, 1962.