When developing his strategy for the Ardennes counteroffensive, Adolf Hitler knew it was essential to capture at least one intact bridge over the Meuse. Given his ambitious goal of driving a wedge between the U.S. and British armies, crossing the Meuse, and advancing to the coast at Antwerp, speed was crucial to Hitler’s plan. If the Germans failed to capture an intact bridge over the Meuse, the resulting delay would give the Allies time to recover from their element of surprise and assemble troops west of the river before the Germans could cross. To prevent this, Hitler assigned Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Otto Skorzeny a special mission called Operation Greif.

Hitler summoned Skorzeny to his headquarters in October 1944 to personally deliver his orders. Skorzeny had previously led secret missions for Hitler, including the rescue of Benito Mussolini, but this would be his largest and most complex. He was tasked with equipping and training a commando unit that would advance alongside the 6th Panzer Army—the vanguard of the northern offensive. In addition to capturing at least one bridge over the Meuse, the commandos were to wreak havoc in the Allied rear through espionage and sabotage.

To achieve this, Skorzeny relied on deception, deploying English-speaking soldiers in US uniforms and equipment. Hitler explained to Skorzeny that the Allies had used the same ruse in recent battles. He assured his loyal command that disguising themselves as Americans only violated the laws of war if the German soldiers went into battle disguised.

Skorzeny established his command in Grafenwöhr. With only six weeks of preparation time, he had a lot to do. Hitler promised unlimited support, but like most of his claims regarding the Ardennes counteroffensive, this was an exaggeration that didn’t pan out. Skorzeny received significantly less American equipment than expected: only a few dozen jeeps, trucks, and half-tracks, plus one Sherman tank. To compensate for this shortage, he equipped his main force, Panzerbrigade 150, with approximately 70 German tanks disguised as American armored vehicles.

In a major breach of security, German Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel sent out a message seeking English-speaking volunteers from across the Wehrmacht to serve in a special unit commanded by Skorzeny. Around 2,000 men responded to this message, which also caught the attention of Allied intelligence officers. As it turned out, most of the volunteers knew little more than a smattering of English. Only ten were fluent, and a few dozen more could carry on a conversation. Skorzeny organized the best English speakers into the Stielau unit —a reconnaissance element made up of teams of two to six men, equipped with jeeps, radios, and some explosive devices. Most of these men had no commando experience, and with only six weeks of preparation, they had time for only rudimentary training.

During their training, a rumor spread among the commandos that their mission would involve the assassination of U.S. General Dwight Eisenhower. Despite Skorzeny’s attempts to suppress the rumors, he was undeterred. Soon, American intelligence officers also heard this rumor. Ironically, this led to arguably the mission’s greatest success. When the counteroffensive began on December 16, 1944, reports quickly surfaced of German soldiers disguised as Americans operating behind their own lines. These reports spread and led to significant overestimates of the number of commandos involved in the operation. However, enough were captured to make the threat seem real and significant. Many of the captured commandos told their captors that assassination squads were hunting high-ranking Allied officers, prompting Generals Eisenhower and Bradley to remain in their headquarters to avoid detection. This severely hampered their ability to respond to the German attack.

Although the threat to the American generals was never as serious as feared, the commandos of Stielau’s unit succeeded in creating chaos within the Allied lines. One squad, posing as a traffic controller at an intersection, sent an entire regiment in the wrong direction. Another disrupted communications between General Bradley’s headquarters and the First U.S. Army command post. While the commandos were far too small to carry out all the actions later attributed to them, their acts of sabotage, whether real or imagined, disrupted the American response to the counteroffensive and severely impacted their morale.

The German counteroffensive took the Allies completely by surprise, but soon faltered due to stronger-than-expected resistance. Skorzeny’s plan for Panzerbrigade 150 called for a rapid breakthrough, allowing his camouflaged troops to infiltrate the American lines. However, this was not to happen. On the second day of the attack, Skorzeny realized the game was up and ordered the brigade to operate as a conventional unit and be subordinated to the 1st SS Panzer Corps. Skorzeny’s fight ended abruptly when he was wounded in the face by artillery near the Hotel du Moulin in Ligneuville, Belgium.

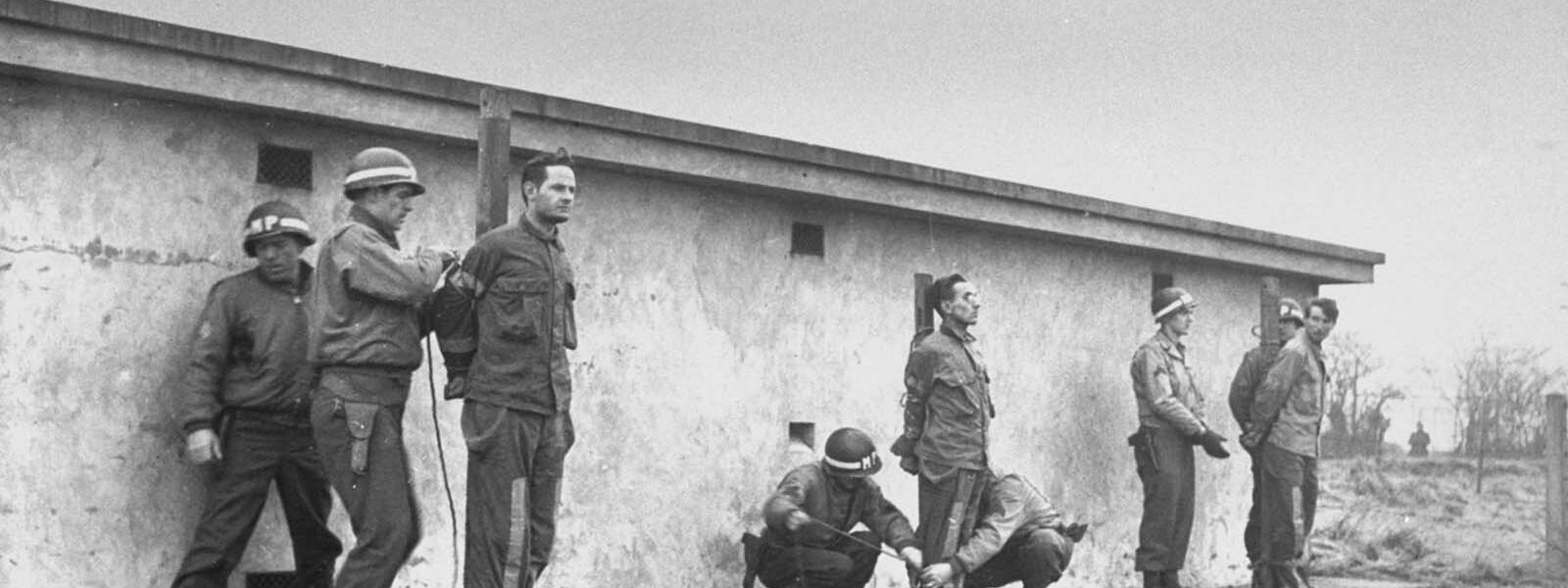

Meanwhile, Skorzeny’s commandos continued their mission, but most were killed or captured by American troops. Only one team returned to German lines. On December 18, 1944, U.S. troops captured three members of the Stielau unit in Awaille, Belgium: First Ensign Günther Billing, First Corporal Wilhelm Schmidt, and Corporal Manfred Pernass. On December 21, a military commission convened at the U.S. 1st Army’s Master Interrogation Center in Belgium. The commission indicted the defendants and found them guilty of two charges: violation of the laws of war (by appearing in theater of operations in American uniforms) and espionage (by gathering information for the enemy in disguise). The commission recommended the death penalty for all three commandos.

Colonel E.M. Brannon, a judge on the staff of the Supreme Court, conducted the necessary review of the proceedings the following day and confirmed the court-martial’s findings. Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges, Commander of the First U.S. Army, approved and confirmed the verdicts that afternoon. The Provost Marshal carried out the executions the following morning, December 23, 1944.

Skorzeny himself was not held accountable for his role in Operation Greif until after the end of the war. In May 1945, he surrendered to the 30th Infantry Regiment and subsequently spent two years in pre-trial detention. The high-ranking Nazi officers tried at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg did not fare well; most were sentenced either to death or to life imprisonment. In August 1947, Skorzeny’s trial finally began before the General Military Government Court in Dachau. In his testimony, he admitted his role in the commando operation, but with the help of his able US-appointed defense attorney, Colonel Robert Durst, Skorzeny’s account began to sway the court. He pointed out that American soldiers had worn German uniforms on several occasions, such as during the fighting at Aachen, and he insisted that he had ordered his commandos to remove their American uniforms before entering combat.

Finally, the surprising testimony of a Royal Air Force officer, Wing Commander Forest Yeo-Thomas, persuaded the court in Skorzeny’s favor. Yeo-Thomas, a British agent known to the Germans as “The White Rabbit,” described how he had escaped German captivity by disguising himself and several fellow prisoners in enemy uniforms. He argued that this was no different from Skorzeny’s use of American uniforms to disguise his commandos. Unlike the military commission that convicted Schmidt, Billings, and Pernass, the Dachau court acted on the basis of international laws of war, which considered the wearing of enemy uniforms a war crime only if the defendant participated in combat while wearing that disguise. Based on this interpretation of the law and Yeo-Thomas’s convincing testimony, the court dropped the charges against Skorzeny and his co-defendants.

Skorzeny remained in prison until July 1948, awaiting the decision of a denazification court. He then escaped with the help of three former SS officers disguised as U.S. military police. He later claimed to have escaped with U.S. assistance. In 1952, Skorzeny was living in Spain when a former German general with ties to the CIA recruited him to train the Egyptian army. He later lived in Argentina, where he was rumored to have been an advisor to President Juan Perón and a bodyguard to his wife. In the 1960s, he was recruited by the Mossad, although his motives for collaborating with the Israelis and the missions he carried out remain a matter of speculation. He died of lung cancer in January 1975 and was cremated after his funeral in Madrid. His ashes were returned to his hometown of Vienna, where former SS officers attended his funeral. He remains a subject of controversy. Some consider him a blatant racist and war criminal, others admire him as a courageous adventurer and pioneer of commando tactics.